Michael Martens reviews Shkëlzen Gashi's detailed book on 83 massacres during the Kosovo War, documenting crimes by Serbian forces and reprisals, using diverse sources. The author's merit is to summarize and offer data that is revealing new or updated information about the victims, the perpetrators and the search for justice.

In March 1999, NATO began bombing Yugoslavia, which by then consisted only of Serbia and Montenegro. This was the first time in its history that NATO launched an attack on a sovereign state. At a special party conference held by the German Green Party in Bielefeld, Germany’s then foreign minister Joschka Fischer gave what became known as his “paint-bag speech1”, in which he justified the first combat deployment of German soldiers since 1945: “Auschwitz is incomparable,” Fischer said. “But I stand by two principles: never again war, never again Auschwitz, never again genocide, never again fascism.” Fischer’s bombastic reference to Auschwitz later drew a great deal of criticism, as did the unproven claim of Defence Minister Rudolf Scharping (SPD) that the Serbians had a plan, called “Operation Horseshoe”, for the expulsion of the Kosovo Albanians from the country.

Even today, the justificatory excesses of the time tend to distract people from a more important fact: NATO’s war against Serbia (with Montenegro as a secondary theatre) was not only justified but also tragically overdue. Had U.S. President Bill Clinton and the Western alliance taken resolute action against the regime of Serbia's brutal ruler Slobodan Milošević and his henchmen a few years earlier, the Srebrenica genocide could have been prevented, and the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina could have been ended much sooner.

Shkëlzen Gashi’s Chronicle of the Massacres

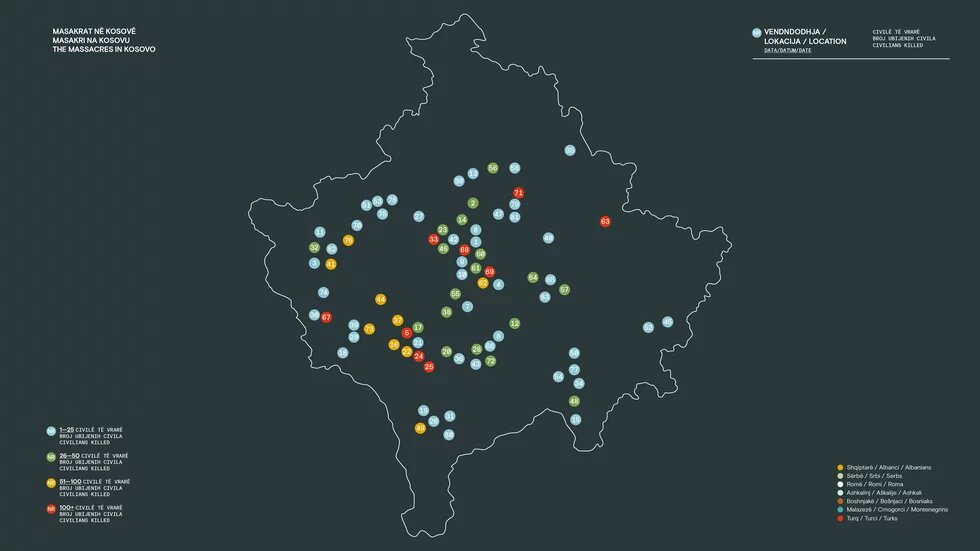

In his book “The Massacres in Kosovo 1998–1999”, Kosovar historian Shkëlzen Gashi depicts what happened in his homeland in that period. This rigorously researched work, published as a trilingual edition (Albanian/Serbian/English), is more a reference book than a single continuous historical account. It describes, in exhaustive detail, 83 massacres in the same number of chapters. These massacres took place in Kosovo between February 1998 and July 1999. In other words, the book covers a period starting more than a year before the launch of the NATO bombing campaign in Serbia and ending in the month after the withdrawal of Serbian forces from Kosovo.

While the vast majority of the massacres in this period were massacres of Kosovo Albanians committed by Serbian soldiers, police officers, or guerillas, there were also some revenge massacres committed against Serbian civilians after the June 1999 withdrawal of the predatory Serbian combatants from Kosovo, i.e. with the newly arrived Western troops already on the ground. These are also described in the book. Gashi also explains that some of the massacres of Kosovo Albanians were preceded by deadly attacks on Serbian uniformed personnel by guerilla fighters from the "Kosovo Liberation Army" (UÇK).

According to the Belgrade Center for Human Rights, more than 10,300 civilians were killed in Kosovo between 1998 and 2000, nearly 8,700 of them Albanians.

After attacks of this kind, the Serbs often did the same thing that the German occupiers in the Balkans had done during World War II: surrounded and shelled the village from which the attack originated or one located near the site of the attack and shot the (male) members of its population, whether they were combatants or civilians. In Kosovo's case, the women, children, and the elderly tended to be expelled to Albania or Macedonia rather than shot, but there were also times when indiscriminate murder was the rule.

Gashi, a historian who never shrinks from criticising nationalist tendencies, even those manifesting in his own country, is methodical and thorough in his research. His reconstructions of the individual massacres are based on a broad range of sources, including the surveys conducted by the Belgrade Center for Human Rights, which laid the groundwork for further research in this field. According to the Belgrade Center, more than 10,300 civilians were killed in Kosovo between 1998 and 2000, nearly 8,700 of them Albanians. About 1,200 Serbs were among the victims, and the others were members of the Roma or another minority.

Gashi also considers reports from Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, the International Crisis Group, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, and various foreign journalists who covered the conflict. Additional sources for his reconstruction of the crimes include judgments of Serbian and Kosovar courts, as well as material from the UN International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in The Hague, whose archives, containing thousands of testimonies and other documents, are a unique resource for historical research.

Escalation of Violence During the War

One is struck by how many of the survivors recalled the slogans shouted out by the killers during the massacres: "Go to Clinton!" or "Albania is your country! Kosovo is ours!" Another pattern emerges when one looks at the timeline: although massacres were committed in Kosovo before NATO began bombing Serbia—Gashi describes 15 such cases—it is clear that Belgrade systematically escalated the attacks after 25 March 1999, when the airstrikes on Serbian positions and infrastructure began.

In the first week of the war, Serbs carried out almost two dozen massacres in Kosovo, killing more than 1,000 people. The systematic expulsion of ethnic Albanians began. While “Operation Horseshoe” may well have been a fiction invented by the West before the war to justify an intervention, just such a plan was now actually being implemented, with the NATO attacks serving as a smokescreen. People were murdered in mass shootings, homes were looted and set ablaze.

The aim was to banish any thought of return from the minds of survivors. Hundreds of thousands of Albanians fled Kosovo ahead of the Serbian killing machine. Milošević's propaganda claimed that it was actually fear of NATO’s bombs that were driving the Albanians out of Kosovo (incidentally, the responsible "information minister" at the time was Aleksandar Vučić, now Serbia’s president). Despite the fact that NATO bombs did not fall over Kosovo's villages, there are still those in the West who willingly spread the propaganda lie that the NATO bombs caused the refugee exodus.

Unlike in Bosnia, where the Srebrenica genocide, in which over 7,000 people were killed, came to symbolise the multi-year policy of “ethnic cleansing”, no one single crime in Kosovo has become synonymous with Serbia's policy of wrongdoing. The largest massacre there took place in April of 1999, when Serbian police and military units killed 350 men in the villages of Meja and Korenica in response to the killing of four Serbian police officers (one Albanian and three Serbs) by Albanian guerrillas. The murdered villagers were members of the Catholic minority of Kosovo’s Albanian population.

Justice, Denial, and the Legacy of War

None of the Serbian men directly involved in this massacre were ever convicted. However, the members of Serbia’s political leadership responsible for this policy did stand trial before the Hague Tribunal. A former deputy prime minister was sentenced to 22 years imprisonment; the chief of the general staff of the Serbian army received a 15-year prison sentence. Sentences ranging from 14 to 22 years were issued to several Serbian generals and police chiefs stationed in Kosovo. Serbia’s own War Crimes Chamber also convicted some of the leading figures involved in the crimes. That was several years ago, though.

The Serbia of today is ruled by the man who was behind Serbia’s claims at the time that the crimes never occurred or that NATO was to blame for them. In this Serbia, the men who committed these crimes have nothing to fear.

first published in German as „Geht doch zu Clinton!“ in F.A.Z., 18.03.2025, Michael Martens

© all rights reserved. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung GmbH, Frankfurt. Provided by Frankfurter Allgemeine Archiv

Recording of the event on March 5, 2025 I Booklaunch & Discussion

Documenting "Massacres in Kosovo 1998-99" - a step towards reconciliation?

Documenting „Massacres in Kosovo 1998-99“ – a step towards reconciliation? - Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung

Watch on YouTube

Watch on YouTube

Footnotes

- 1

[1] Farbeutelrede in German. Before giving the speech, Fischer had been struck on the head by a bag of paint hurled by a protestor at the conference, at which the federal delegates of Greens/Alliance 90 met specifically to discuss Kosovo, then a fiercely divisive issue for the party. The conference was held on 13 May, almost two months into the bombing campaign.