The European Union should work together with partners in Africa to secure electoral systems against cyberattacks, to protect voters and vulnerable groups from abuse of their personal data and to defend against the spread of false and misleading information. This is also in line with European interests and values.

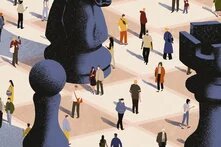

Globalisation fatigue runs high in the 2024 election cycle, in which more than half of the world`s population is going to the polls. Voting is ongoing in India, where Hindu nationalist Prime Minister Narendra Modi is expected to win a third term. Rightwing ‘anti-European’ parties hope to secure considerable gains in elections to the European Parliament in June. And the presidential election in the United States this November is shaping up to be a tight race between President Joe Biden and his populist predecessor Donald Trump who faces criminal charges.

The outsized public attention to elections in leading power centers may distract from many other places where democratic stability is on the line in 2024. In the aftermath of military coups, presidential elections were postponed in Mali and Burkina Faso, further delaying the restoration of democratic governments. Elections in Namibia and South Africa could see liberation parties lose their long-held majorities. While this may indicate a maturing of the democratic system, there is uncertainty about how elected officials will adapt to necessary power sharing. These are amongst 19 countries going to the polls on the African continent, where disinformation campaigns attributed to Russian, Chinese and domestic actors have gathered steam and threaten to polarise societies.

EU and Africa have limited platform ownership

The abovementioned African countries may seem far removed from the world’s power centers, but what happens there has repercussions for Europeans and Americans, and vice versa. Election interference and voter manipulation are a globalised business, in which internet platforms act as amplifiers of hate speech and false information, often exacerbating the ironically nationalistic, ethnocentric, or at times xenophobic turn in public mood in many countries. The EU and Africa are in the same boat as they have limited ownership of the platforms and technologies that are used to mislead or sow confusion. The advent of generative AI has potentially exacerbated the problem by adding video and audio to the types of content that can be manipulated - or straight-up invented - with just a few clicks.

Working with partners in Africa to secure electoral systems against cyberattacks, to protect voters from abuse of their personal data and to defend against the spread of mis- and disinformation is in line with European interests and values for the following reasons:

Disinformation is a two-way street - Disinformation and voter manipulation trends are mutually reinforcing, and actors behind such campaigns often use countries with comparatively weak regulatory systems as testing grounds. The now infamous Cambridge Analytica, which harvested data from US Facebook users to help the Trump campaign create voter profiles for targeted advertising in 2016, had been active in Kenya as early as 2013. After gay marriage was legalised in the United States, US evangelical groups exported anti-gay disinformation narratives to countries like Uganda, where they fell on fertile ground.

Destabilisation in Africa creates risks for Europe - Disinformation by external actors can destabilise countries in Africa, creating geopolitical risks for Europe. Almost as soon as Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, false claims about the war began circulating online in Africa. One key narrative in social media and articles – according to an analysis of reports published by Africa Check – was that Russia enjoys broad support on the African continent and vice versa, based on their historical ties. This narrative can easily be linked to Moscow’s geostrategic ambitions. Other narratives exploited growing negative sentiments against France, especially in West Africa. For example, as calls for French forces to leave Niger grew, so too did praise of alleged Russian support for the country. After the coup in July 2023, demonstrators in Niger’s capital Niamey waved Russian flags in scenes similar to what occurred in Mali in 2021 and Burkina Faso in 2022.

Human security of vulnerable groups - Risks of false information, data breaches or abuse are magnified in countries with large vulnerable communities. As Research ICT Africa states in a report on security risks of artificial intelligence – from AI-enabled cyberattacks to AI-enabled surveillance systems, “AI security risk is unevenly distributed and disproportionately affects those who are least prepared and capable of dealing with it, especially in Africa.” For example, whereas women everywhere report being subjected to online hate speech, women in patriarchal societies or women of colour are even more exposed to online threats or discrimination. The same is true for the LGBTIQ+ community in many countries – as organisations like ‘Let’s Walk Uganda’ have documented.

EU should reach out for its own benefit

The EU is currently struggling with erosion of trust in its own information system and democratic institutions and is searching for the right ways to protect citizens from online abuse. In addressing these issues, it should not only reach out to African governments, but also to the media and the civil society, who may need assistance but who can also inform Europe’s understanding of the cross-border nature of these risks.

Cybersecurity. Africa needs assistance, training, and resources for securing infrastructure and uncovering foreign influence campaigns. In January 2024, digital forensics experts hired by the German Foreign Ministry uncovered a pro-Russian disinformation campaign on X. Not all countries have the resources to conduct or finance such operations. The challenge can be that some countries draw a murky line between cyber security and national security, creating a difficult environment for investigations aimed at exposing foreign or domestic influence campaigns.

Information sharing. Providing resources and support to research, independent journalism and fact-checking organisations in African countries can help uncover disinformation networks – and ultimately help disarm them. Africa has an expansive network of homegrown civil society organisations that would benefit from funding, training and collaborations with partners in the Global North. The above-mentioned analysis of reports by Africa Check, for example, made possible with support from the European Digital Media Observatory, highlighted similarities in Russian narratives being shared across both Africa and Europe. To effectively counter disinformation, partnerships across different geographical regions are necessary. Migration, foreign policy, climate change, and health are some of the topics that could benefit from such cross-continental cooperation.

Governance. All aspects of digital governance converge in the task of countering disinformation: cybersecurity, data protection, platform regulation and AI regulation. The EU has a lot to offer when it comes to advising African countries based on its own mature regulation. Lack of resources is a key challenge for African countries trying to enforce new data protection laws or African versions of the EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA). Nevertheless, the verdict is still out on whether the DSA can increase accountability in the June elections for the European Parliament. Illustrating the need for mutual learning, the Irish Council of Civil Liberties recommended that the European Commission should consider provisions in the African Union guidelines on tech and elections in drafting its own election guidelines for very large online platforms, released on 26 March. The AU recommendations went beyond the EU’s with a ban on processing certain data by recommender systems and the protection of sensitive voter data in online advertisement bidding.

Content moderation. Platforms have increased outreach to Global South stakeholders, and collaborate with media and researchers. For example, Africa Check is a member of Meta’s third-party fact-checking programme, which identifies and addresses misinformation on the platform. The former has also collaborated with X (formerly Twitter) and TikTok on election-specific projects. Overall efforts are still spread unevenly between North and South, and between languages.

Fact-checking and digital literacy. Several studies suggest that fact-checking can support media organisations in need of verifying information, and that it can correct misperceptions and discourage people from sharing unverified information online. At the same time, false information cannot be held back one claim at a time. It requires a multi-pronged approach, including pre-bunking, which means that people are directed to sources that offer verified information before they encounter false claims. Mis- and disinformation are less likely to thrive in an environment where people have a certain level of digital literacy, i.e. they can easily access quality information on key issues and are taught the skills to fact-check for themselves.

Exchange with Africa to keep the EU honest

When it comes to globalised disinformation, Africa is both part of the problem and of the solution. Some African countries are leapfrogging technologies, for example in providing e-government services for voters or using AI for voter registration and cyberthreat detection. The African Union and many member states have passed well-informed legislation and policies on issues ranging from data protection to AI, raising Africa’s profile in global conversations on digital governance such as the UN’s Global Digital Compact.

For the EU, this conversation brings opportunities for alignment as well as challenges, for example in cases where African governments do not champion a rights-based approach. Across the continent, ruling parties frequently employ internet shutdowns to suppress unwanted information – especially during election seasons – harming freedom of expression. The EU is right to speak out against authoritarian practices, but it has to beware of hypocrisy. Legitimate criticism of surveillance practices is undermined by carve-outs for ongoing exports of such technologies by European companies or for their use by immigration authorities. In that sense, a stronger African voice on EU laws and practices may also be needed for keeping the European debate more honest.