The almost 70-year history of the ESC reads like a seismograph of the cultural and socio-political situation in Europe on many levels.

Over the course of its almost 70-year history, the Eurovision Song Contest, or Grand Prix d’Eurovision as it was once known, has grown into a media spectacle that has become an integral part of public life in this country. The contest is polarising, stirring great enthusiasm among its devoted fanbase, but also leaving its critics shaking their heads in disapproval. Love it or hate it, each May, the ESC is all over the media and practically inescapable. It even has a solid fan base in Australia and the USA thanks to its entertainment value, variety, and diversity. The number of participating countries has swelled from just seven contestants (Switzerland, Italy, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and Germany at the first contest in Lugano in 1956) to an all-time total of fifty. According to the European Broadcasting Union, 162 million viewers watched the broadcasts of the final and the two semi-finals in 2023, making the ESC the largest music competition in the world.

The beginnings: Le Grand Prix

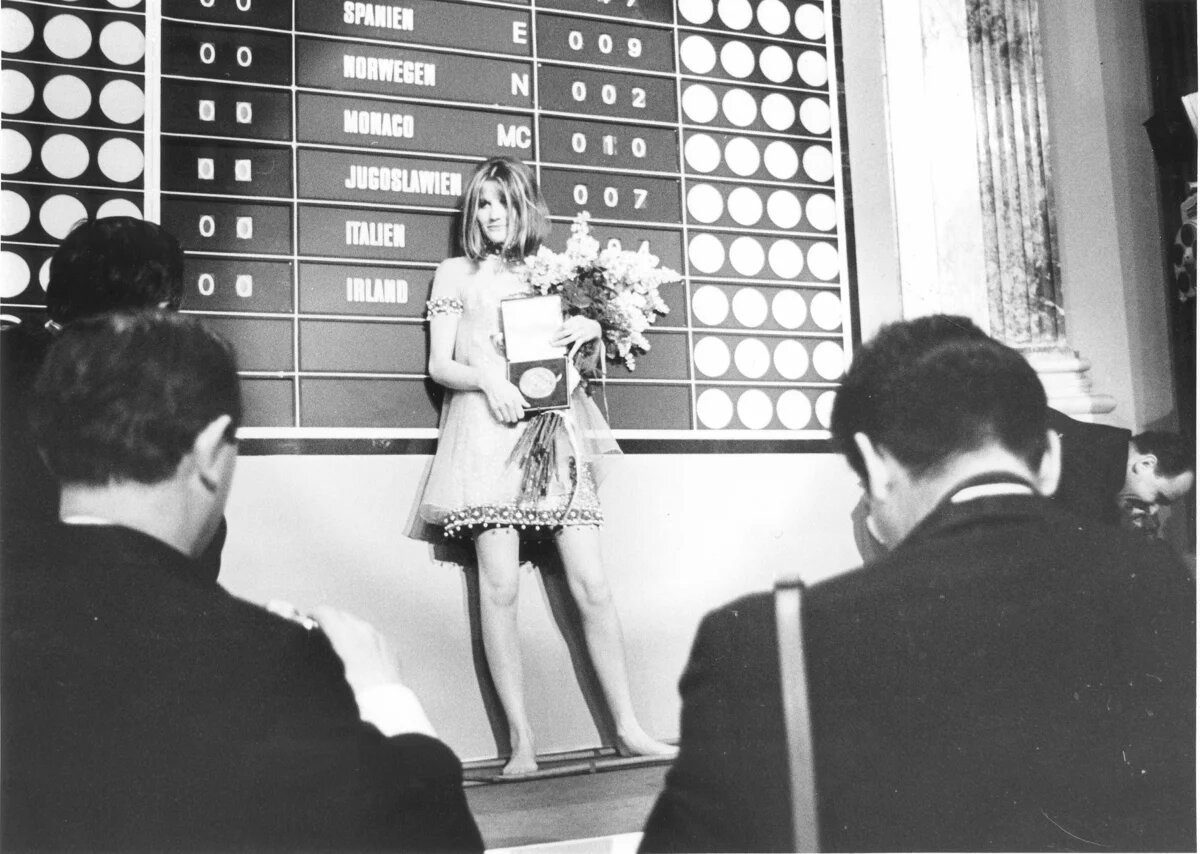

In 1956, however, things looked and sounded quite different. Most followers listened to The Grand Prix on their radio sets at home, which means that back then, the word “grand” may have referred to quality rather than scope. The live audience in the concert hall appeared in suits and evening gowns. The European Broadcasting Union launched the contest in an effort to boost the domestic music market. To be eligible, an entry had to be an original composition of no more than three minutes. The contestants were neither the countries nor the performers, but the composers, commissioned by their respective national broadcaster. Of course, this aspect has been somewhat lost today. In any case, we should note that to this day, there are no rules regarding either the composers’ national origin, nor the language of the song lyrics. (A language rule was in place from 1966 to 1972 and from 1977 to 1998, however.) The Eurovision format fed the young medium of television entertaining programming content that was accessible in the Member Countries of the European Broadcasting Union across different languages. As more and more households purchased TV sets in the 1950s and 1960s, a growing audience was able to watch the contest on television.

The community-building and emotional effect of music could well set the mood for a broader political consent.

Back then, the orchestra and conductor were important musical and visual features of the performances. It not only impacted the sound and style of the songs (mainly chansons and Schlager), but also symbolically celebrated cultural dialog as the baton passed ceremoniously from one conductor to the next. The main objective was to leverage the language of music to promote cultural exchange across national language barriers. A televised musical entertainment programme seemed to be an adequate medium to create communities around the medium. Although the event was a contest, its intent was by no means to stir any political or national rivalries. To this day, the rules of the Eurovision Song Contest expressly prohibit political content in the songs and performances. A mere decade after the end of World War II, the need to seek comfort in seemingly apolitical popular music is understandable. But is it a coincidence that the very same countries that participated in the first Grand Prix (except Switzerland) signed the Treaty of Rome ten months later in March 1957, laying the foundations for the European Union? Music may not be able to prompt political decisions, but its community-building and emotional effect could well set the mood for a broader political consent.

Eurovision as a mirror of the socio-political status quo

In many ways, the almost 70-year history of the Eurovision Song Contest reads like a seismograph of the socio-political situation in Europe and beyond. The performances, the presence or absence of certain countries, the winning acts, the hosts’ commentary, and the news coverage all reflect European post-war history as well as processes of division and integration. If you listen closely, events such as the Prague Spring, street riots in Belfast, the Carnation Revolution in Portugal, the end of the Franco dictatorship, the Cyprus conflict, the eastward expansion of the European Union, the Orange Revolution, and the war of aggression in Ukraine all echo in some of the songs. To name just two examples: In 1982, Nicole sang “Ein bißchen Frieden” (A little bit of peace) in four languages, capturing the spirit of the times and the longing for peaceful coexistence in the shadow of the NATO missile crisis. In 1990, Toto Cotugno’s anthem “Insieme – Unite, unite Europe” captured the hopeful and joyful mood after the fall of the Berlin Wall. In 2022, the political dimension of the media spectacle became clearer than ever when Ukraine’s Kalush Orchestra won the contest in a landslide and the United Kingdom stepped in as host country the following year.

In 2022, the political dimension of the media spectacle became clearer than ever.

Yet as we know, the conflict between Ukraine and Russia began much earlier, both in brutal reality and in the media utopia that celebrates community and transcends borders. When Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, the competition barely responded to the event. Both the Ukrainian and Russian contestants delivered their entries, which had been selected long before the aggression. It wasn’t the Ukrainian singer, but Austrian winner Conchita Wurst who became the target of hostility from Russian conservatives. In the following year, the war in Donbass prevented Ukraine from participating. Yet their absence from the competition went largely unnoticed – quite symptomatic of Europe’s general response to Russia’s acts of oppression. In 2016, Ukraine was back on the Eurovision stage and making its voice heard all the louder with Jamala’s song “1944,” a tale about her family history and the deportation of Crimean Tatars as well as a call for more humanity. Forty-two participants answered that call the following year when Kyiv hosted the contest for the second time. Russia did not participate. It was only after the Russian attack on Ukraine on February 25, 2022, that the Reference Group of the Eurovision Song Contest decided to suspend Russia for disregarding the values of the contest: cultural understanding, diversity, and peaceful coexistence. The Ukrainian delegation was flooded with expressions of solidarity. Their song “Stefania” was inevitably received as a protest song, even though it was composed well before the invasion. Did the Kalush Orchestra win only because of empathy for and solidarity with Ukraine? Or was it actually a solid composition and a great performance? The song combined different cultural elements: folkloric vocals in the chorus, modern rap in the stanzas, and an instrumental hook on the telenka. The performers were a diverse group of six men, dressed in both traditional garb and modern clothes. They encouraged the audience to dance, clap, and sing along with their performance, even though only few understood the lyrics.

Musical diversity

In fact, it is precisely this eclectic cultural diversity that makes the contest and its entries so attractive. Just looking at and listening to the Ukrainian contributions since their debut in 2003, the musical diversity of the songs is striking: They are an eclectic mix of ethnopop, hip hop, techno, disco, folklore, pop ballads, trip hop, and rock. They innovatively integrate traditional musical elements like folkloristic flutes, historical vocals, and specific harmonies. The entire 70-year history of the ESC and with its over 1,600 songs constitutes a rich and unique visual and musical archive of recent music history in Europe and beyond, whose hallmark is musical and cultural diversity. The ESC started out with chansons and Schlager. Today, the entries cover all possible varieties of popular music. In addition to the above-mentioned genres, they also cover jazz, blues, disco, gospel, Latin, Balkan pop, reggae, heavy metal, EDM, opera, and singer-songwriter compositions.

It is precisely this eclectic cultural diversity that makes the contest and its entries so attractive.

A perusal of the archive shows that over the decades, the music of the contest has always been evolving, absorbing new trends in popular culture. In the early 70s, youth culture began to permeate the rather serious affair that the ESC had been in the 50s and 60s. The 80s were all about fashion and style. By the end of the 90s, in one of the most drastic visual and musical changes in the history of the composer-based contest, the live orchestra was replaced by a playback. However, this change also allowed for greater musical and creative freedom and more modern instruments and synthesizer sounds. The stage design also kept getting more creative, elaborate, complex, and technical from year to year. Today, the artistic design is a key vehicle to help convey the impact and message of the songs.

In addition to musical and performative developments, historical footage from the contest is also an inventory of technical innovation over the last seven decades. Camera work and technology has changed, the quality of live broadcasts has improved, and their reach has increased. All these developments are preserved in the archive of ESC entries for everyone to hear and see. Today, the Eurovision Song Contest is an immersive audiovisual media spectacle leveraging the latest digital technologies.

United in diversity

As more and more countries joined the contest, the ESC stage became ever more diverse and colourful. Anything was possible, no matter how crazy and weird, as long as it stayed within the three-minute limit. Global trends and local styles have converged in the performances, generating many surprising acts. Time and again, the acts feature visual and musical elements that refer to specific cultural traditions in the presenting countries. The success of such national elements does not depend on their authenticity, but rather on how the material, which sounds and looks exotic to outsiders, is combined with the familiar. Overall, this broad musical diversity can be read as a musical mirror of the cultural diversity of Europe and beyond, as well as for the diversity across various generations of audiences that have come together over decades to form one media community.

In general, this media spectacle is all about engaging the audience, stirring emotion through music, surprising the audience, and perhaps even making them laugh (or shake their heads). With their performances, the contestants want to leave a lasting impression and make the audience feel like they are part of this Eurovision community. Music is the vehicle that instils this sense of community. Viewers in front of tv sets and other screens become part of this community, which is centred in Europe, but radiates to various other parts of the world. They feel connected to each other and can interact with the live event by televoting. It is interesting to note the different status of the ESC in different countries and the level of attention it has received in different years. This has not yet been empirically studied, but the longevity of the contest proves that there has been continuous interest in it, manifesting itself in both enthusiasm and criticism. Everyone seems to have an opinion on the ESC, and every opinion is valid as long as it doesn’t conflict with the values of cultural diversity, openness, tolerance, and integration. You don’t have to like a performance, but you should appreciate the composers’ and performers’ hard work, creativity, and effort that goes into each entry. Some performances may even provoke extreme reactions and polarise intentionally. But in the end, it’s the same music that unites Eurovision fans. The fact that everyone can be their authentic selves, both on stage and in the audience, is a small achievement of the ESC that has hardly ever been possible in any other context of such scope and public impact. The ESC offers space for grand emotions, the idea of justice, and equal gender representation. So does that mean that an ESC song can change the world? Not likely. But it can make the world seem like a better place, at least for a moment. Can the Eurovision Song Contest exist in an apolitical vacuum? It certainly cannot. On the contrary, ESC officials should be aware of its political dimension and address it responsibly. As utopian as it may seem, the contest can offer an alternative setting where a heterogeneous community comes together every year to promote cultural diversity and understanding. Even if it is only once a year, for one Saturday evening.

Prof Dr Saskia Jaszoltowski teaches musicology at the University of Graz. Her research interests include music and media history (especially film music) as well as the study of political, aesthetic, and economic interdependencies in music culture.

Translation: Kerstin Trimble.