Isidora Weibel Díaz reflects on protests of young Chileans and the state brutality during the riots from 2019 until 2022 and discusses the context and consequences for Chilean society.

“When we lost the plebiscite, I felt defeated, I thought all the struggle and sacrifice had been in vain," comments Nahuel Herane with a cigarette in his hand, who at seventeen lost his left eye, after members of the Chilean police shot him with a pellet at close range while he was participating in the 2019 uprising.

Herane, who today is twenty years old and studies history, is one of the five hundred and seventy-two minors who reported having been tortured, stripped naked and shot by Chilean state agents during the social unrest, according to figures from the state-run National Institute of Human Rights (INDH).

"I thought it was all for nothing"

“The ophthalmologist told me that I had had an eye burst, so I was never going to recover the vision in my left eye," says Nahuel Herane (20), a history student who lives in Villa Portales, in the Estación Central district.

On 21 December 2019, Herane took seven pellets to different parts of his body while demonstrating outside his apartment. The shots were fired by police officers. He was seventeen years old.

“In the village where I live, we have been working in a territorial way for years. For example, I belong to an Andean dance group and we always organize carnivals. When the protests began, I met my neighbors again, which was very nice," he says.Nahuel Herane complains that when he returned home after his eye operation, the police began to harass him constantly. “There were Carabinero motorcycles outside my house, patrols passed by all day, they even called my neighbors asking for me. We had to call the prosecutor in charge of my case to tell her about the situation. She called the police station and they never came back”.

When he won the option to reject the constitutional proposal, Herane was overcome with emotion. “I thought it had all been for nothing, the loss of an eye, the energy expended. Afterwards, you still understand that political processes are like that. We must not blame the people, but we must remember that nothing has changed, there are still people in prison and repression continues”.

“Boric is one more concerta (sic)," he says in allusion to the former members of the Concertación, the center-left alliance that governed the country almost uninterruptedly since 1990, applying neoliberal and privatizing policies that maintained the economic and social regime inherited from the dictatorship.

The demonstrations, which according to the Prosecutor's Office left an in-tray of 8,581 judicial complaints against the police and the Armed Forces, began on 18 October 2019 when thousands of schoolchildren evaded the turnstiles of the subway train in Santiago de Chile, days after the authority decreed a fare hike, equivalent to only four cents on the dollar.

The government of businessman Sebastián Piñera (2018-2022), a historic right-wing leader, responded to the mobilizations by deploying police inside the Metro. Television screens around the world were filled with images of beaten, detained and bleeding minors in a matter of hours.

But why did protesters and authorities react with such vigor in the face of a marginal price increase in a country with a per capita income of $14,500, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF)? “In Chile, income for the vast majority of people is insufficient to cover all the goods and services they need,” explains historian Andrea Sato of Fundación Sol.

According to Andrea Sato, the protests were triggered by “The lack of income, a level of indebtedness that has increased systematically, the commodification of all social rights, and an absent State whose function has become one of mechanisms and strategies for subsidizing capital and not improving living conditions.”.

Catalina Ramírez (31), a social work student who also participated in the student marches of 2006, says that when the social protests began, they manifested themselves as a mutual outpouring of emotions following years of neoliberalism and democracy with little citizen participation.

“I knew something was about to break, but there was also fear because of what we had been told about the 1973 coup d'état (against the socialist government of Salvador Allende). I had the feeling that something could change and that was a future for our children," says this mother who lives in Recoleta, a lower-middle-class community located north of the capital.

Three years later, despite thousands of marches, some involving millions of people, the political picture has changed radically. The extreme right almost won power in the December 2021 presidential elections and the proposal for a new Constitution was defeated in the September 2022 referendum. This is the story of a country that has oscillated from the collapse of neoliberalism to the threat of fascism in just months.

The first hours and weeks

On Friday night, 18 October 2019, twenty subway train stations were burned by protesters, who erected barricades and clashed with police throughout Santiago, a city of some seven million inhabitants, where the average income of workers that year was around six hundred dollars a month.

Piñera - who ten days earlier had said that Chile was an "oasis in a convulsed Latin America" - reacted by indefinitely suspending public transportation in the capital and invoked the state's Internal Security Law to repress the protests. She then went to eat pizzas with her grandchildren at a restaurant, located in one of the richest neighborhoods in the country, unleashing a wave of criticism.

In just hours, the demonstrations spread over more than four thousand kilometers of the country, whose GDP per capita at current dollars is similar to that of Spain, Portugal and Greece in 2000, but without a robust social security system. Public universities charge fees of four to seven hundred dollars a month and surgical care can take years in the state health system.

As a result, ports, roads, schools and public services came to a standstill. Airports were also closed. In response, on 19 October, without giving in to the demand to freeze the four-cent increase in the subway fare, Piñera decreed a state of emergency and a curfew in the capital, deploying thousands of military personnel to the streets.

“We are at war against a powerful, implacable enemy, who respects nothing and no one, with the sole purpose of producing the greatest possible damage. They are at war against all Chileans of goodwill," the President declared on television on 20 October. By then there were millions of demonstrators in the streets.

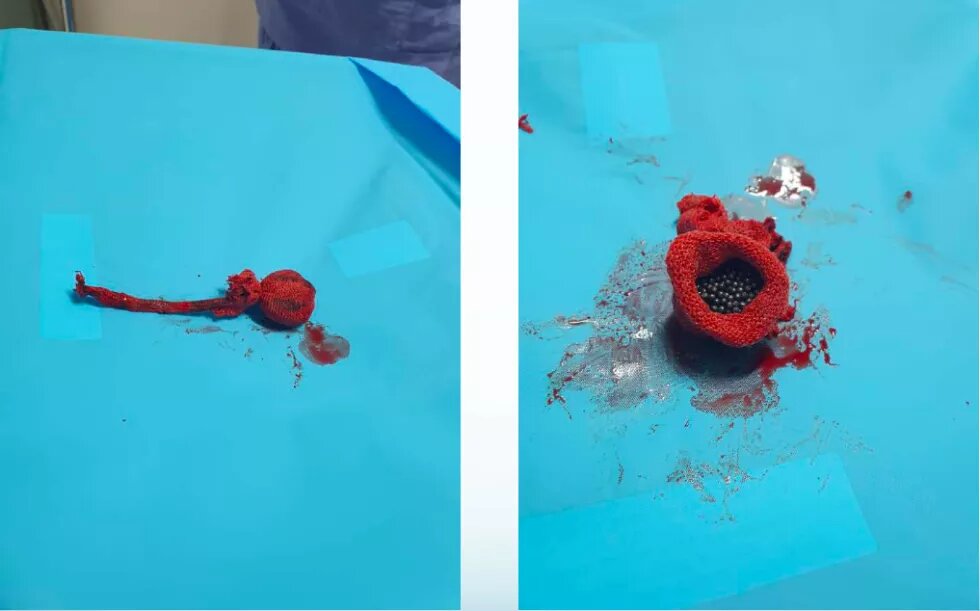

Three days later, in a secret document, the general director of Carabineros, Mario Rozas, asked the government to open the Army's arsenals, since his institution had run out of ammunition. At the end of December, the police ended up firing more than 152,000 rounds of ammunition containing over 1,800,000 pellets at the civilian population. The forces of law and order also launched 140,000 tear gas bombs, according to official figures.

Some 400 people suffered eye damage and mutilation. Another 1,132 were injured by pellets. “I thought about buying a bulletproof vest. It was surreal to encounter a completely militarised police force. These people had direct orders to shoot at the body and went further, shooting at the eyes," denounced photographer and artist María Jesús Püeller (34), who recorded the demonstrations on a daily basis.

“When they deployed the military onto the streets, I was terrified, but at the same time, I felt strong, because of the stories I have been told about the dictatorship. I felt that all the people were on the same side, we were not a few fighting against many. That gave me courage," recalls Catalina Ramírez.

The President of the Human Rights Department of the Medical Association, Enrique Morales, who has kept systematic records of cases of police torture since 2011, denounces that human rights violations were widespread in all regions of the country and were characterized by a definite pattern.

On the physical side, he highlights "the use of pellets, the impact of projectiles from tear gas bombs, beatings with both fists and metal batons on various parts of the body, the running over of demonstrators with police vehicles and burns due to the incorporation of some chemical agent, the identity of which we are unaware, in the water cannons”. They also observed sexual violence such as forced stripping, touching in sexually suggestive places and the threat of rape.

“We also saw psychological violence," Morales adds, "such as the simulation of an execution, threats to involve them in major crimes such as looting or carrying Molotov cocktails, the threat of suffering or witnessing a beating or sexual abuse”. According to the specialist, most of the people evaluated by the mental health teams had at least acute stress syndrome or post-traumatic stress disorder.

“Police violence," comments Catalina Ramirez, "has always existed with the same brutality. The big difference is that now we have evidence and it goes viral thanks to digital social networks”. In this regard, Enrique Morales confirms that since 2011 his team has observed the use of paintballs and pellets, "even causing eye damage, in a smaller number”.

During the uprising, the country was paralyzed and the demands grew. Demonstrators attacked police stations and regiments, ransacked supermarkets, entered regional seats of government and in the presidential palace of La Moneda, there were no political answers to the social demands, which ranged from sectoral issues to the change of the neoliberal Constitution of 1980.

At this crossroads, some three million Chileans marched across the country on 25 October, half of them in Santiago, in a mobilization of some thirty blocks along the Alameda, the capital's main avenue.

“Increasingly, broad sectors of society did not see the political system as the way in which they could resolve their social conflicts. This has been going on for fifteen years, for education, health, pensions (provided by private companies)," says sociologist Carlos Ruiz, a leftist intellectual close to the Frente Amplio, now in power.

“Capitalism in its neoliberal phase as a system is in a crisis of meaning. It is directly related to an unfulfilled promise of growth and development, which does not reach everyone," adds Chile's first transgender congresswoman, Emilia Schneider (26), who reached the lower house after heading the Federation of Students of Chile (FECH).

For the same reason, Schneider believes that the protests experienced in Latin America in the last three years are mediated by the political crises experienced by liberal democracies around the world.

A constitutional path

In the midst of human rights violations and massive protests, on 15 November 2019 the ruling parties and broad sectors of the center-left opposition reached an Agreement for Social Peace and the New Constitution, which established an electoral and political timetable to replace the neoliberal Magna Carta, established under the civic-military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990), and which for decades has allowed privatization of everything from the provision of social rights to water.

The pact, from which some left-wing parties such as the Communist Party withdrew due to procedural differences, implied that the country's new framework law would be drafted by a Constituent Convention after the citizens confirmed in a referendum their will to replace the 1980 Constitution.

That first plebiscite was held on Sunday 25 October 2020, one year after the largest march in Chile's history. Despite the pandemic, 50.95 percent of voters turned out to vote, a significant figure for the country considering that voting was voluntary at the time.

At the close of the polls, the option to draft a new Magna Carta won with 78.31 percent of the votes. The proposal that the constituents should be elected in their entirety by the citizens was almost equally supported, rejecting the possibility that the Convention should also be composed of parliamentarians.

The Constituent Convention, where the constitutional proposal was drafted, was made up of one hundred and fifty-five representatives. It was the first in the world to be composed of gender parity and with seats reserved for indigenous peoples (17), in addition to promoting the participation of people with disabilities.

“I was excited about the constituent process, I understood that it was good and that it was a step forward. However, afterwards we could continue to fight to reform it in certain aspects," says Nahuel Herane.

The high number of Covid-19 infections caused the constituent elections to be postponed for five weeks, finally taking place on 16 May 2021. More than 6.4 million people participated, corresponding to 43.35 percent of the electoral roll. No one thought at the time that this process would culminate in failure.

The first warning sign came on 21 November 2021, when the first round of the presidential elections for the 2022-2026 term took place. Against all odds, José Antonio Kast (56), leader of the far-right Republican Party, won with 27.9 percent of the vote. The leader of the left, Gabriel Boric (36) obtained 25.7 percent of the votes.

Kast, a former supporter of General Pinochet, put forward a program that proposed the creation of secret prisons to combat the left, granting the President the power to decree provisional prisons and the reduction of women's rights. Some of the candidates for parliament who supported him suggested repealing women's suffrage, such as the ultimately elected MP Johannes Kayser.

For the presidential run-off, Gabriel Boric managed to mobilize broad sectors of the female electorate, finally triumphing with 55.87 percent of the votes, becoming the youngest president in the history of the country.

However, not all those who supported Boric wanted a change like the one being articulated in the Constituent Convention. The support for the current President was, in many cases, a vote to prevent Kast's rise to power.

The first great challenge of the new government, and its first great defeat, was the plebiscite of 4 September 2022, an election in which the citizens were to ratify or reject the proposed new Constitution.

That constitutional proposal defined Chile as "a social and democratic state governed by the rule of law. Plurinational, intercultural, regional and ecological". It also enshrined fundamental rights such as health, education, recognition of domestic and care work, the right to housing, adequate food, the human right to water and sanitation, and the right to live in safe and violence-free environments. It always spoke from a gender parity and gender perspective.

Poor institutional and electoral communication together with the proliferation of rumors and misinformation helped to hinder the constituent process in several circumstances. “I feel I could have been more informed. I liked a lot of what the constitutional proposal addressed, but it looked sketchy in terms of detail. It was going to be a total failure," admits Erik Pinera (18), a physics student from the Puente Alto district, a lower-class sector with a high percentage of social deprivation. He finally voted against it.

Emilia Schneider, who participated in the Apruebo campaign, confesses that they did a poor job - "We started late, we were disorganized. We had causal data that we were always going to have less money and with the media against us. Our communication policy was very conservative and traditional", regrets the congresswoman.

“The lack of solemnity, the show of some constituents, the meager connection with the popular masses, little experience in press management and overconfidence" were some of the mistakes that former constituent and public administrator Marco Arellano (33) recognizes were made and influenced the winning of the option to reject the constitutional proposal.

“We went too far”

Marco Arellano (32) has been a leader and environmental activist for several years in the commune where he lives, Quilicura, a vulnerable district of the capital.

When the protests began in 2019, he understood that it was a historic moment to bring about change and that he had to participate in the Constitutional Convention. “It was difficult to run as an independent, but we won the election and came out ahead representing District 8”.

He admits, discouragingly, that several mistakes were made in the constituent process and that at times it was difficult to coexist with the other representatives. “I would have liked some colleagues to be more solemn. When you are there, you have to understand that you are thereby popular consent, which is greater than personal ideals”.

“I tried to do my job calmly, avoiding involvement in any controversy. I understood that seriousness and respect for certain republican traditions are important for people in Chile," he adds.

In his opinion, the constitutional work was "very progressive for Chilean culture and Chile’s population”.

“The issue of plurinationality was key, it was a new concept. We went further than the population wanted," he concludes.

“The lesson we must learn is the importance of collective projects and the strengthening of them. We are facing a social explosion while the political parties, social movements and student federations are very weak. There is a crisis of participation," concludes Emilia Schneider.

Fascism emerges and the new constitution falls

In terms of numbers, the 4 September 2022 referendum had a historic turnout of thirteen million people. The option to reject the constitutional draft won with 61.86 percent of the votes (7,882,238). This means that the Constitution imposed by the civil-military regime of the dictator Augusto Pinochet is maintained.

“Social dynamics are not linear. The extensive mobilization that took place in 2019 did not entail the maturation of a subjectivity capable of overcoming the mercantile and individualistic logics that prevail in important social segments," reflects sociologist Omar Núñez, regarding the defeat of Apruebo.

Following the same idea, Carlos Ruiz adds that "people are asking for a new Constitution anyway. We are in a very open historical cycle where there may be many exits. In no country and in no era have such large transformation processes been so short and linear. It's about progress and setbacks”.

Former constituent Marco Arellano also believes that the constitutional work was very progressive for Chilean culture and its population. “Respect for certain republican traditions for the people is important, but it was not understood by all constituents equally within the Convention”.

Andrea Sato says that since October 2019, people's material conditions have worsened tremendously and that, if people's living conditions do not improve, they will herald a new period of national protests. “We are in a much deeper crisis today than we were thirteen years ago. Looking to the future cannot be done only through the leadership of national governments; instead, we must also think about community and territorial constructions. Chile must generate collective sustainability and welfare mechanisms; they cannot continue to be individual”.

At present, the political parties are trying to reach a new constitutional agreement, but this time with less potential for transformation. The idea of including seats for indigenous peoples is questioned. As is the idea that the new Constitutional Convention be composed while adhering to gender parity or entirely composed of representatives elected by the citizens.

What is at stake are the edges of the country's new legal framework and without mobilizations in the streets, the conservative sectors have less pressure.

Times of impunity

But there is not only a constitutional crisis.

“It is quite discouraging to know that the Boric government promised an amnesty for prisoners taken during the uprising and has not kept its word," says Nicolás Piña , a young engineer who spent thirteen months in preventive detention in the overcrowded Santiago Uno prison. He was charged with attempted murder and throwing Molotov cocktails, even though he tested negative for hydrocarbons. “I am now on probation, must sign in weekly at a police station and my grandmother's house is under bond.”.

“They treat you like you're society's trash"

“The hardest thing was being away from my children," says Nicolás Piña (35), one of the most renowned prisoners of the 2019 uprising.

He was arrested on 12 February 2019 while demonstrating in the capital's central Plaza Dignidad with his mother. He was arrested by the so-called Intramarchas, i.e., police officers who infiltrated the demonstrations, with the purpose of carrying out follow-ups, arrests and imprisonments, despite not having authorization from the judge or instructions from a prosecutor.

Piña spent more than thirteen months in pre-trial detention in the Santiago Uno concession prison while his investigation was underway. He was denied his freedom three times.

“When they take you prisoner, they let you know that you are guilty and that you will not be able to prove your innocence in any way. They still accuse me of attempted murder and throwing a Molotov cocktail without having hard evidence. In fact, one of the tests they did on me was for hydrocarbons and it came out negative”.

He says that living with others inside the prison was sometimes good and that he used to hang out with other inmates from the uprising, known as the "bomb prisoners”. “They treat you like you're society's trash. It's bad. Inside the prison, you learn what frustration is like, what it's like to be told no, to be humiliated. Prison is hard and it's not for everyone, you have to have great mental strength," he says.

Piña is currently on probation (he cannot leave the country), must sign in weekly at a police station and his grandmother's house is under bond. “It is quite disheartening to know that this government promised an amnesty for those taken prisoner during the protests and has not kept its word", he laments.

In addition to the thousands of people arrested during the mobilizations of 2019 and 2020, at least 177 people were imprisoned in various prisons across the country, according to press reports collected by parliamentary committees. Most of them, after long months of imprisonment, were released due to lack of evidence or because the accusations were based on false testimony by the police.

But there are also problems with human rights investigations. Lawyer and academic Myrna Villegas criticize the significant level of impunity in Chile. “Progress must be made in the clarification of human rights violations. HH. Gabriel Boric's government (2022-2026) wants to talk about reparations, but we cannot do so without having resolved the damage that was caused”.

For her part, Alejandra Arriaza, a lawyer for minors, criticizes the fact that the police forces have protected themselves and withheld information. “They destroyed the cameras, they do not cooperate when summoned to testify and say they were acting to safeguard public order. They refuse to hand over anything, ranging from the lists of those who were present to the weapons they were using”.

“The Public Prosecutor's Office," explains attorney Karinna Fernández, "has the duty to investigate, prosecute and punish all crimes committed against people, particularly those belonging to vulnerable groups. However, since the uprising began, they have not complied”.

For Villegas, there are also political debts. “The Chilean State must solve the issue of the people taken prisoner during the protests. The President of the Republic has the power to pardon several of the political prisoners who are condemned and has not done so," criticizes the academic, an expert in criminal law.

Three years after the social protests began, the state-owned and autonomous National Human Rights Institute (INDH) has filed 3,151 complaints with the Public Prosecutor's Office. Of these, 551 are for acts of torture, 660 for unnecessary violence, 2,232 for unlawful coercion and eight for deaths caused by state action. Only thirteen sentences have resulted in convictions for those responsible.

This essay was produced with the support of the Global Support for Democracy Unit of the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung European Union. It is part of the dossier "Youth & democracy in Latin America. Young voices on the rise".