Hopes about a new thaw in transatlantic relations might evaporate soon. With respect to its key ally in Europe, the US is not only expecting an increase in German defense spending, but also a realignment of Berlin's China policy.

Few countries are more hopeful about a renewal of transatlantic relations after Joe Biden’s victory in the US presidential election than Germany. Calls from Berlin for a fresh commitment to transatlantic cooperation include a wide range of policy issues from the current COVID-19-pandemic to climate change, digitalization, trade and defense.

More specifically, Germany’s defense minister Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer has offered a “New Deal” to the incoming Biden administration. This new bargain offers an expansion of German military spending, a renewed German commitment to NATO’s nuclear sharing, and a new US-EU free trade agreement, all in exchange for ensuring that “America continues its commitment to defending Europe”. Apart from a vague reference to a common transatlantic agenda where this is “compatible with [German] interests”, Kramp-Karrenbauer’s offer says little about China.

Conflict of interests in transatlantic relations

From the perspective of the incoming US administration, the proposed New Deal will not be enough. Germany and Europe have lost the significance to US foreign policy they once held. Driven by a desire to “get tough” with China, the incoming US administration will not be satisfied with a German military build-up, proposals for transatlantic free trade, or a commitment to nuclear sharing. Instead, if the German government wants Washington to consider its defense a “joint project”, Germany will need to pay a much higher price by rethinking its economic relationship with China, Germany’s largest trading partner. Unless it is willing to make painful economic concessions, Kramp-Karrenbauer’s offer for a post-Trump transatlantic reset will not receive an affirmative response from Washington.

Kramp-Karrenbauer is right: the transatlantic partnership needs an update to its strategic rationale. Barack Obama’s announcement of America’s ‘pacific century’ and his government’s ancillary role in the Libyan intervention, both in 2011, were the first signs of a soft, yet determined reorientation of US attention to East Asia. Donald Trump’s sustained abuse of NATO and his questioning of US security commitments exacerbated what is a growing mismatch between what the US expects from Europe and what Europe can provide.

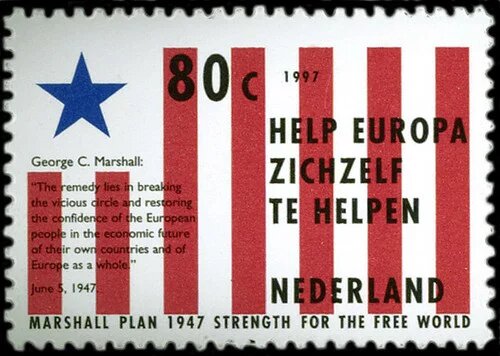

This has not always been so. From the founding of NATO to the end of the George W. Bush administration, transatlantic relations were based on a clear strategic bargain. During the Cold War, the United States extended security guarantees to Western Europe, undergirded by its nuclear umbrella and hundreds of thousand forward-deployed US troops, in exchange for a European commitment to anti-Communism. After 1990, the US kept its guarantees in place, even extending them to new NATO members, in exchange for European military and financial support in an ever-growing number of military interventions, so-called out-of-area operations.

Nowadays, Joe Biden, once a prominent supporter of the 2003 Iraq War, pledges to “end the forever wars”. Without a US interest in large-scale military interventions, Europe’s support for out-of-area operations is no longer needed. Both sides of the Atlantic seem to agree that it is time for a new strategic rationale if the transatlantic relationship is to remain relevant. There are, however, significant differences in what a new transatlantic bond requires.

Multilaterism of the USA

Take multilateralism. To the German government, the term means a US return to the guardianship of the “house of the West”, expecting the American guardian to protect and support an international free trade order that has immensely benefited the German economy in past decades. To the incoming US administration, in contrast, multilateralism means building a “united front” of allies and partners against China, Germany’s largest trading partner. Confronting China as a burgeoning global power from a “position of strength”, as Biden’s nominee for secretary of state, Tony Blinken, recently demanded, implies an inevitable skepticism towards new trade deals and a Trump-esque desire for “fair trade”, not free trade. When Biden’s own advisors argue that the liberal international order has failed to “lure or bind” Beijing as was expected, it is no surprise that the incoming administration would be reluctant to return to the pre-Trump status quo ante Germany is so dearly missing.

Not only Kramp-Karrenbauer’s proposal to negotiate a comprehensive free trade deal between the EU and the US is likely to fall on deaf ears in Washington. Similarly, while her calls for higher German defense spending and a renewed German commitment to NATO’s nuclear sharing might serve as an attempt to stake out a position in domestic German debates, they are unlikely to convince Washington. Decreasing US interest in Europe was not caused by Germany’s reluctance to reach NATO’s often-cited two-percent spending goal, but by a strategic reorientation of US grand strategy. A German military buildup and recommitment to nuclear sharing will not reverse this course.

True, Joe Biden is fundamentally more sympathetic to the EU and NATO than Donald Trump ever was. In a phone call with German chancellor Angela Merkel, Biden stressed that transatlantic cooperation would become a priority in his foreign policy. Indeed, quick progress on the fight against the COVID-19-pandemic and climate change should be expected. Yet, deeper cooperation will depend on Germany’s willingness to serve as a political and economic counterweight to China. The US focus on countering the rising Asian power will not stop with Biden, and with Trump gone, Germany and Europe will have a harder time playing both sides of the fence. As much as this puts Berlin in an awkward position, the road towards a new strategic rationale for transatlantic relations leads through China.